After attacking Devil’s Reef in 1928, the U.S. government rounded up the people of Innsmouth and took them to the desert, far from their ocean, their Deep One ancestors, and their sleeping god Cthulhu. Only Aphra and Caleb Marsh survived the camps, and they emerged without a past or a future.

The government that stole Aphra’s life now needs her help. FBI agent Ron Spector believes that Communist spies have stolen dangerous magical secrets from Miskatonic University, secrets that could turn the Cold War hot in an instant, and hasten the end of the human race.

Aphra must return to the ruins of her home, gather scraps of her stolen history, and assemble a new family to face the darkness of human nature.

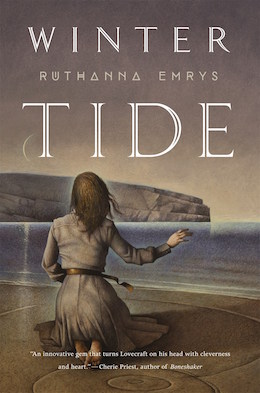

Ruthanna Emrys’ debut novel Winter Tide is available April 4th from Tor.com Publishing. Head back to the beginning of this new Mythos tale, or read on for chapter 5 below!

Chapter 5

We left the library late, and with a promise that my list of books would remain available on the morrow. At Spector’s plaintive query, Trumbull led us to the faculty spa, which even in the intersession served food well after the ordinary dinner hour. Tall men hunched in corners, gesturing with pipes and murmuring in low tones over wine and steak.

The books all bore marks from the families that had owned them. Even in the moral primer, a young Waite had drawn tentacles and mustaches on illustrations previously lacking either, signing “OW” proudly in the corners. Obadiah Waite had died of heatstroke our first summer in the camp, at the age of six.

As of yet, we’d found no Marsh records. I was ashamed at my gratitude for the delay.

I’d forgotten hunger easily in the mausoleum of the library, but now discovered myself ravenous. As warm clam chowder recalled me to the living world, I considered Trumbull. My subconscious had marked her as a predator from the first—she had a strength and viciousness almost certainly necessary to survive Miskatonic’s academic and political grottos. She ate as deliberately as she did every thing else, but gave no sign of noticing the quality of either the food or the company. The others stole glances at her as well. She looked at none of us, but when I turned away I felt her attention like the barrel of a gun.

Spector’s motivations, the danger he presented, I was learning to understand. I did not know what drove Trumbull, and her interest in my people frightened me.

As I considered that fear, a draft of cool air hit us. I looked up to see Dean Skinner stamping snow from his boots as he took off his hat. He saw us and smiled, an unpleasant expression considerably more confident than any he’d shown earlier.

He moved through the room, stopping at several tables to converse quietly. Laughter drifted from shared jokes, and a couple of people glanced in our direction as they spoke with him.

At last he came over and clapped Spector on the back. “Mr. Spec-tor. I trust you’re settling in well. Does it look like you’ll be able to find what you wanted?”

Spector stiffened, then returned an answering smile that seemed a deliberately transparent mask. “Too soon to tell, I’m afraid. But thank you for asking.”

“You’re my guests on campus. Miss Marsh, Miss Koto, I trust Professor Trumbull is seeing to your needs. It’s good to have more ladies here, from time to time—brightens the place up.” I worried that he might try to touch one of us as well, but Trumbull gave him one of her dry looks, and he stepped back. “Excuse me, it looks like they have my drink ready. I’ll catch up with you later, I’m sure.”

I didn’t get a chance to talk with Caleb before we dropped the men at Upton Dormitory, where the door guard confirmed that guest rooms had indeed been reserved. Neko and I continued on with Trumbull, and Neko walked closer to me than the frigid night warranted. My breath escaped in bursts of warm fog. Though I knew it was foolishness, I mouthed a prayer to Yog-Sothoth, keeper of gates, for safe passage through this season.

Trumbull had been honest about the state of her house. It was neat enough, and well- dusted, but still gave an impression of staleness and disuse. She directed us to sheets and guest beds, and left us on our own to combine them. We did so without complaint.

Sometime after the lights were out, I felt Neko’s weight settle on my mattress.

“Are you awake, Aphra?”

“Entirely. How do you like travel?”

“It’s exciting, but cold. And I wish you had books in English. Or Japanese.”

I laughed in spite of myself. “You’d have needed to meet us much earlier, for Innsmouth to have books in Japanese.”

“Would it have made a difference, do you think?”

I shook my head. I could see easily in the cloud-dimmed moonlight, but suspected she could not. I put my arm around her. “Two despised peoples, together? We’d have ended up in the camps a decade earlier.”

She shrugged. “It still upsets people now, and I don’t think staying apart would help. Being out here on his own hasn’t helped Caleb.”

“No, it hasn’t.”

We curled together in the narrow bed, sisters sharing warmth. I breathed the remains of her floral perfume, the mammalian sweat beneath it, and eventually fell asleep.

Recently, Charlie and I had been practicing wakeful dreaming. He looked forward to the more advanced skills of walking between dreams and gleaning knowledge within the dream world—for me it was sufficient that when I woke in endless desert, throat too dry and hot to breathe, I knew it for illusion. I forced back the panic, the desperation for air and moisture, and imagined breath until it came to me, harsh and painful. I did not yet have the strength to change the desert to ocean, or even to the comfort of snow or fog.

I do not need to dream. There is a real body, a real bed—and by repeating this mantra I awoke at last, gasping.

Neko still slept beside me. I slipped out from the corner of the bed where my struggles had carried me and went in search of water.

Eye-stinging electric light burned in the dining room. I halted on my way to the kitchen as I saw Trumbull bent over a spread of books and papers. She cocked her head.

“Bad dreams.” She stated it as a fact, and not a particularly interesting one.

“Yes,” I admitted. “Sorry to disturb you; I was only going for a drink of water.”

“The salt is beside the sink.”

I had my first blessed sip of water, and poured a little salt in it to wet my face. Only then did it occur to me how much she must already know, to offer me salt water as casual comfort. I considered what I had seen of her so far, and considered also the courage it must have taken Charlie to hazard his guesses about me.

If she were something worse than I suspected, it would be best to know quickly.

I stepped back into the dining room and asked in Enochian, “How far have you journeyed?”

“Space beyond measure, aeons beyond understanding,” she replied in the same language. She turned around. “You’ve been slow, water child. Memory should be a guide, not a distraction.”

I knelt, placing my glass on the floor beside me. “I’m sorry, Great One. I had not expected to find you here.”

“One of us is frequently in residence at Miskatonic,” said the Yith. “Too many of this era’s records pass through their gates to neglect the place. And they offer resources for travel and study that are otherwise inconvenient to seek out.”

She turned back to her papers. Waiting for a member of the Great Race to ask me to rise might be a good way to spend the night on the floor; doubtless she had already forgotten it was not my natural posture. I took a seat at the table.

She ignored me for a few minutes, then looked up. “Do you plan to ask me for an oracle? Hints of your future?”

Probably I should. “Do you enjoy doing that?”

“No. It’s tedious.”

I considered what I might learn from her, given the opportunity. But it was late, and when I cast about I found only the past that I should not ask about, and trivial concerns. “When the original Trumbull gets her body back, will she be startled to find that she has a professorship at Miskatonic?”

“Don’t be foolish.” She ran a finger down her sleeve, as if suddenly noticing the body she wore. “Our hosts must possess great mental capacity, or the exchange would be much less fruitful.”

“It takes more than intelligence for a woman to gain such a position.”

“This is true.” She smiled at her hand, almost fondly. “I find that hosts with a degree of tenacity and”—she paused, considering—“resilience, yes, resilience, make for a more comfortable exchange. Such minds are less likely to waste their time in the Archives on distressed mewling. Also, they are less likely to flood one’s home body with stress chemicals. I don’t like to find my limbs twitching at every statue.”

“That makes sense.”

She looked at me pityingly. “Of course it does.”

I cursed myself for tediousness. “Excuse me. I’d best get back to bed.”

“Certainly. You are young, after all.”

“Isn’t everyone, by your standards?”

She frowned at a manuscript and moved it to a different pile. “Your subspecies lives to a reasonable age. Long enough to learn their arts with some proficiency.”

I made it almost to the hall before I gave in to the question. Turning back, I demanded: “Did you know what would happen to my people?”

“The generalities, certainly. If there are specifics you wish recorded in the archives, you might write them up for me.”

“That’s not what I meant. Would some warning of the raid have been too tedious an oracle for you to give?” I winced even as I said it. My parents would have been appalled to hear me take such a tone with such an entity.

When she turned around, she did not appear appalled or even startled.

“I met the last sane K’n-yan, after her people became the Mad Ones Under the Earth. She demanded the same thing of me. Her name was Beneer.”

It was neither explanation nor excuse, yet the anger drained out of me, to be replaced by all-too-familiar mourning. At this time of night I would gladly have traded it back.

“Iä, the Great Race,” I said tiredly. “Please don’t use my name as an object lesson for the last ck’chk’ck. It will not please her.” And I returned to the guest bed, as I ought to have earlier. When I dreamt of lying parched on a bed amid empty desert, I did not bother to wake myself.

Excerpted from Winter Tide © Ruthanna Emrys, 2017